Venezuela, a country considered as a role model economy for other Latin American countries a few decades ago, has now fallen into deep economic, social, and political crisis that seems to never end. Venezuela’s economy, highly dependent on oil exports, witnessed a steep decline when global oil prices dropped dramatically during 2014-2017, followed by the government ill-treating national funds, and a massive reduction in import of goods. Under this scenario, several multinational companies, such as PepsiCo, Palmolive, and Coca Cola, chose to reduce or temporarily cease production in the country, which has led to increased unemployment. As a result, many Venezuelans started to flee the country in search for a better life quality, while those who chose to stay face low salaries, hyperinflation, empty supermarket shelves, and increasing violence as political turmoil is deepening amid opposition and criticism of the current government of Nicolas Maduro.

The root of the problem

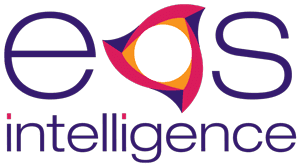

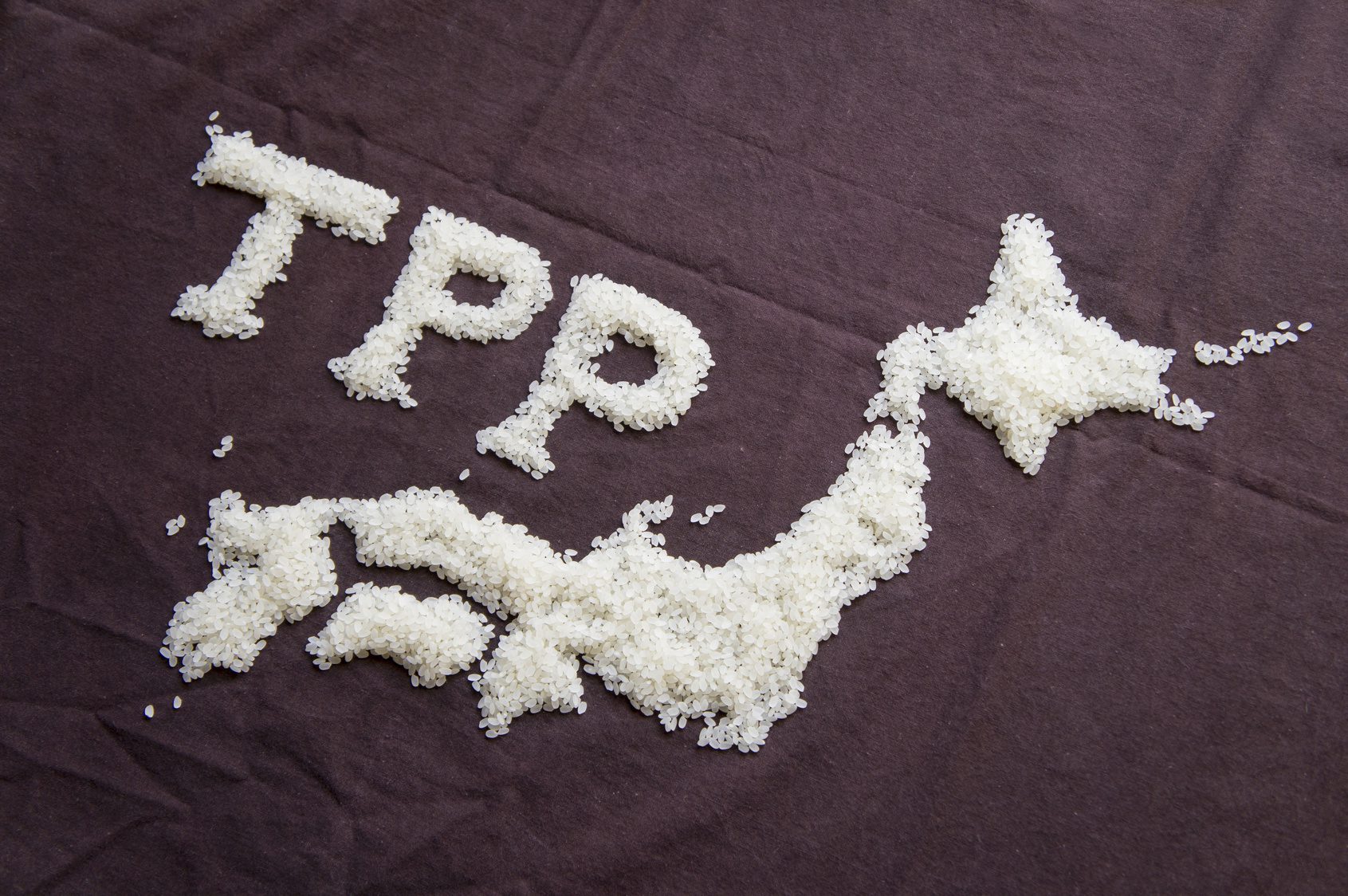

Venezuela’s deep social and economic crisis is driven mainly by mismanagement of national funds and lack of investment in industries of national importance. For several years, the Venezuela’s government-established projects involved providing social aid for households with low income, and these programs were supported by revenue generated through oil exports. Therefore, as gas and oil sector revenue accounts for 25% of the country’s GPD, a steep plunge in global oil prices from US$85 in 2014 to US$36 in 2016 deeply affected Venezuela’s social projects turning them unsustainable.

Venezuela’s deep social and economic crisis is driven mainly by mismanagement of national funds and lack of investment in industries of national importance.

In addition, Venezuela did not invest in its oil industry, one of the main pillars of the country’s economy. Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PVDSA) the Venezuelan state-owned oil and natural gas company has witnessed limited investment, causing Venezuela’s crude oil production to decline from 2.7 million barrels per day in 2014 to two million in 2017, expected to further crumble to 1.4 million barrels per day in 2018. This also translated into a decrease in oil exports revenue by 64% during 2010-2015, deepening scarcity of funds and progressing economic instability in the country.

Plummeting imports in import-dependent economy

Venezuela has been highly dependent on imported goods and raw materials such as food staples and medicines, among other goods. After the fall in oil prices and decrease of crude oil production, Venezuela redirected a large percentage of the remaining revenue from oil export to repay foreign debt, drastically reducing import volume of goods. As a result, imports severely dropped from US$58.7 billion in 2012 to US$18 billion in 2016, leaving the country with shortage of wide range of goods, including pharmaceuticals, sugar, corn, wheat, etc.

Soaring inflation and unemployment

In addition, Venezuela established strict price control regulations as a way to counterbalance hyperinflation, which directly hindered production of goods by multinational companies. Consequently, several key market players reduced or partially stopped operations in the country as a way to avoid losing profits. In February 2018, Colgate Palmolive, a US-based consumer goods company, stopped production for a week after the government demanded that the company reduces the price of its products, which resulted in a large loss in profit for the company. Subsequently, the reduction of multinationals’ operations in Venezuela greatly increased the unemployment rate to 30% as of 2018, causing Venezuelans to opt for unreported employment or to flee the country looking for job opportunities. It is estimated that between one to two million Venezuelans will have migrated by the end of 2018.

EOS Perspective

Throughout 2017, the ministry of urban farming encouraged people to grow food, e.g. tomatoes and lettuce, at their homes and to start eating rabbits as a way to prevent starvation as a result of massive shortage of basic goods. Meanwhile, as a way to ease the situation, Venezuelan authorities sell a monthly bag containing corn flour, beans, rice, pasta, dried milk, and some canned foods at VE$25,000 – this is less than a dollar. These bags with food are distributed only among people registered in the communal councils and those who possess a Carnet de la Patria, a home registry system in order to receive the food. Additionally, president Maduro decided to open 3,000 popular meal centers as part of a nutritional recovery scheme seeking to feed hungry Venezuelans. However, none of these measures have clearly had enough impact to aid in the difficult situation amid the deepening crisis in Venezuela.

Migration to neighboring countries in Latin America has been the way many Venezuelans have found to escape the crisis. Argentina, Chile, and Colombia, among other Latin America countries, have received over 629,000 Venezuelans in 2017 alone, which is 544,000 more Venezuelans than in 2015. The mere number of fleeing people indicates the scale of the issue, yet the socialist administration of Nicolas Maduro refused to accept any help, aggravating the already strained political relationships with his Latin American counterparts. Further, Venezuela also refused to accept any aid from international institutions such as the WHO, which would help as a short-term solution or at least a relief for starving Venezuelans.

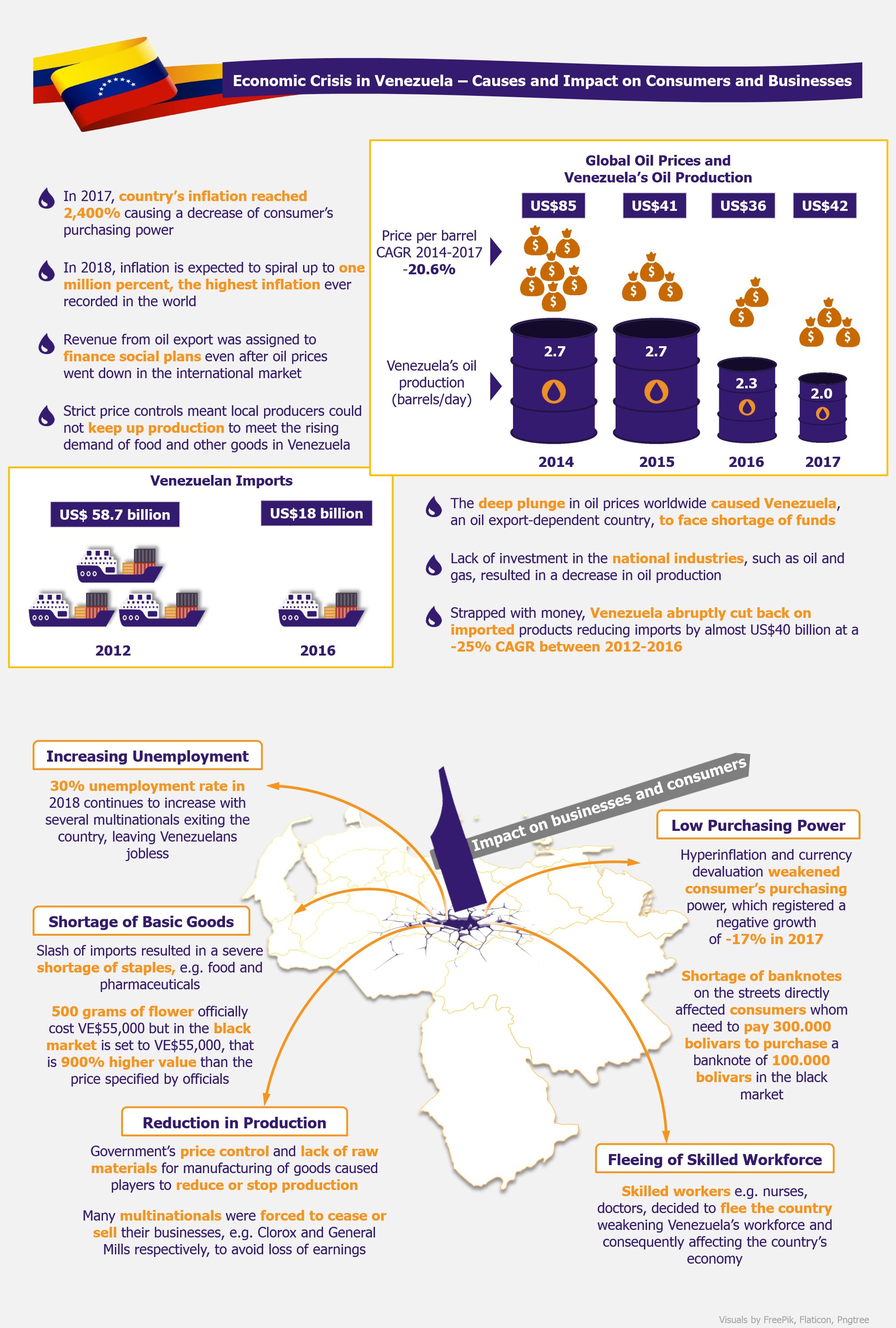

Moreover, Venezuela seems to be continuing to drown, as South American trade bloc Mercosur – one of the most important commercial blocs in the region, suspended Venezuela’s membership indefinitely in 2017. Such a measure translates into further reduction of imports into Venezuela from the bloc and, potentially, Venezuelans banned from legally migrating to any of the countries from the Mercosur bloc. So far, South American countries have welcomed waves of Venezuelans, but the dormant prohibition could negatively affect a considerable volume of the population seeking to flee from the crisis.

Venezuela seems to be continuing to drown, as Mercosur suspended Venezuela’s membership indefinitely in 2017. Such a measure translates into further reduction of imports by Venezuela from the bloc.

In addition, the USA issued an executive order banning any American financial institution from investing in Venezuela, that same year, which restricted the inflow of capital and increased the financial isolation of Venezuela from the North American markets.

This dramatic situation, both in Venezuela’s domestic as well as international arena, calls for president Maduro to reevaluate and encourage reforms that should empower small domestic producers, e.g. coffee makers, agricultural producers, among others, in order to reactivate internal consumption and counterbalance shortage of food and other supplies. Further, it is high time that the country’s leadership opens their borders to external help, however this seems unlikely to happen, considering that this would mean an acknowledgment that the socialist political management of the country has failed, and this in turn would play into Maduro’s opposition’s hands to easily overturn his government.