After 7 years of preparations, Brazil hosted the most expensive FIFA World Cup in 2014 at a cost that totaled billions of dollars. What is the associated outcome of spending huge sums on World Cup preparation? Did the investment leave any positive legacy for the country? What is the economic impact of hosting the World Cup on Brazil?

Investment and Associated Outcome

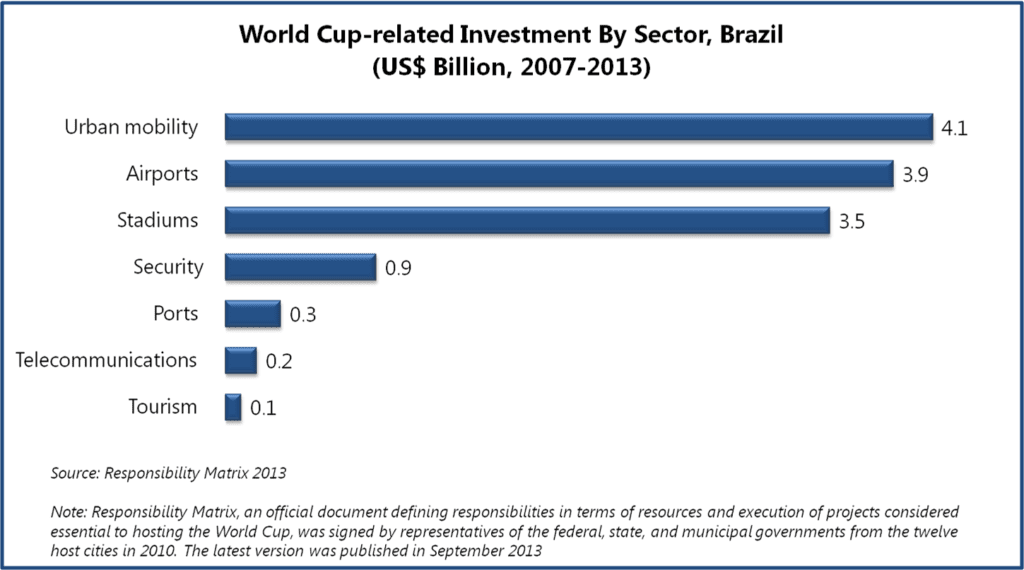

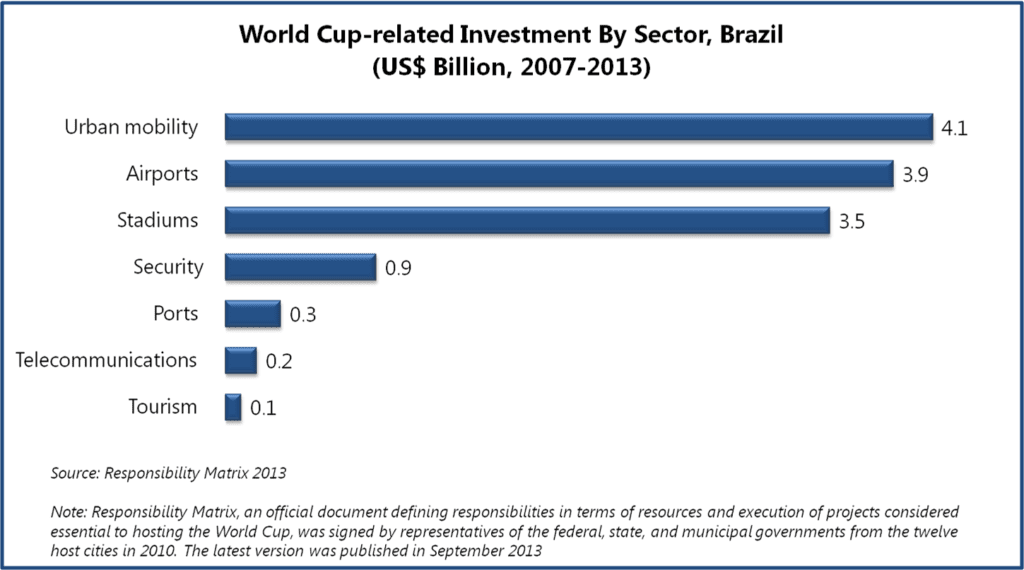

Investment in projects considered essential to hosting World Cup in 2014 varied across a range of sectors and had different impact on each of them. Around US$12.9 billion were invested in numerous projects focused on urban mobility, airports, stadiums, tourism, ports, telecommunication, and security between 2007 and 2013.

Urban Mobility

Brazil has been struggling with overcrowded urban transportation systems for years. The insufficient public systems, paired with Brazilians’ growing financial capabilities, resulted in an increase in personal vehicles use, which in turn triggered chaotic and congested traffic conditions across Brazil’s major cities. 2014 World Cup investments planned in relation to urban mobility were expected to leave positive legacy for the country and to improve transportation systems in metropolitan cities easing traffic problems. But, several delays (caused by corruption, financing problems, etc.) were observed in execution of the planned urban mobility projects during 2007-2012, long before the event. Furthermore, as the World Cup neared, the government’s focus transferred to stadium construction works, as six out of the proposed twelve stadiums for 2014 World Cup still remained incomplete a year before the tournament. According to Responsibility Matrix 2013, investments dedicated to urban mobility projects were cut down to US$4 billion from US$6.6 billion anticipated in 2010. Some 21 of 53 projects planned in 2010 were discarded from the Matrix in 2013. Transformative advancements in transit infrastructure were expected to be the most beneficial outcome from hosting the mega sporting event. But with time, the priorities for government changed, and many of the ambitious projects never took off, as was the case with the proposed project for building high speed train linking Rio and Sao Paulo that was never executed.

Moreover, as the required urban mobility projects remained unfinished during the tournament, government declared holidays in schools and businesses on game days to ease traffic congestion. In June 2014, Sao Paulo State Federation of Commerce, a representative of 155 trade and business unions, estimated that the cost of lost productivity and overtime pay for businesses that remained inoperative during games would be around US$5 billion.

Furthermore, experts allege that these urban mobility projects were approved hastily without giving much thought to long-term benefits, which represents an intangible opportunity cost. For instance, some of the host cities, such as Sao Paulo, Manaus, Salvador, and Porto Alegre, were not allotted any investments in transport infrastructure. In most host cities, the mobility projects were limited to Bus Rapid Transit lines and there were no plans to invest in light rail, metro, or ferry lines.

Airports

An estimated investment of US$3.9 billion was designated to airports, out of which US$2.9 billion were contributed by private sources. These investments led to a noticeable improvement in airport infrastructure and facilities. An assessment report, published in July 2014, by President Dilma Rousseff and the Minister of Civil Aviation Moreira Franco indicated that around 16.7 million passengers used airport services in Brazil during the tournament. In addition, annual passenger capacity at airports increased by 52% over 2013 capacity level, reaching 67 million passengers per year. Between 2007 and 2014, aircraft yards were increased by 1,360 m², passenger terminals were increased by 350,000 m² and 54 new boarding gates as well as 10,300 parking slots were built. Modernized infrastructure and increased capacity will remain as positive legacy for the country.

Stadiums

Between 2007 and 2014, Brazil constructed five new stadiums, renovated five stadiums, and demolished and rebuilt two stadiums for 2014 World Cup. The estimated cost of construction and renovation of the proposed twelve stadiums for hosting 2014 World Cup game increased to US$3.5 billion, up from US$1.2 billion projected in 2007. Public opinion was outraged at these inflated costs, especially that they were paired with un-kept promises once given by the government representatives. After winning the bid to host the World Cup in October 2007, the former Sports Minister Orlando Silva promised, “There won’t be one cent of public money used to build stadiums”. However, according to Responsibility Matrix 2013, the contribution by private sources for building and refurbishing stadiums stood only at US$61.3 million, so majority of the costs were borne by federal investments and state and municipal governments. Another issue associated with the construction of large stadiums is its effect on urban real estate. Each newly built facility is spread across around 15 to 20 acres of urban land, making the space unavailable for any other, perhaps more productive, purposes. It is likely to also continue to negatively affect the real estate prices, especially, as urban land is scarce in Brazil.

Post 2014 World Cup, some cities, which received large stadiums built specifically for the tournament at capacities far exceeding local, every-day needs, are struggling to make these facilities economically viable. In particular, the stadiums built in Manaus, Natal, Cuiaba, and Brasilia appear to be under the fear of turning into ‘white elephants’. These cities have football teams playing in Brazil’s third-fourth division championships, which are not expected to attract the audience at volumes close to the stadiums’ capacities. Moreover, if government fails to find private sponsors for these stadiums, hefty maintenance costs will have to be paid from public funds. The newly built US$325 million stadium in Manaus alone is expected to demand US$3 million for annual maintenance.

Security

In June 2013, mass protests were held across the country during Confederation Cup, a warm-up tournament organized by FIFA to test stadiums, transportation, and security before 2014 World Cup, to express frustration over exorbitant spending by government on World Cup while Brazil still struggled with below par standards of healthcare and education. The protests turned violent with police crackdown and arrests. Following the event, Brazil’s government became alert and tightened up the security measures for the 2014 World Cup to ensure safety of the visitors. 177,000 security personnel were deployed during the tournament and US$900 million were invested in security structures, equipment, and training. Such high spending on security might not have been required if the government had addressed the problems of the country’s citizens in time, or at least had exhibited more understanding attitude to these sensitive in nature social problems.

Ports

Around US$322 million were invested in ports. With more than 90% of trade in Brazil routed through ports in 2012, ports are an important medium for international trade in the country. However, the funds allotment for improvement of ports under the header of World Cup-related investment remained limited as the sector was not assumed to directly impact the event. Between 2007 and 2013, funds were mainly used for modernization of port terminals at Salvador, Fortaleza, and Natal.

Telecommunication

During 2007-2013, around US$200 million were invested in improvement and expansion of telecommunication infrastructure in association with World Cup in Brazil. In order to connect the host stadiums and other official venues of the tournament, a 15,000 km long optical fiber network was installed that enabled to handle 166 terabytes of data during the World Cup. Furthermore, 15,012 mobile antennas were installed across the host cities. A report released post 2014 World Cup by SindiTelebrasil, a national union of telephone companies in Brazil, indicated that the telecommunication networks in the country were successful in handling large traffic volumes during the event. For instance, during the World Cup final match, held on July 13, 2014, between Germany and Argentina, the telecommunication networks managed high traffic volume of around to 2.6 million photos, which is equivalent 1,430 gigabytes of data.

Tourism

Post 2014 World Cup, President Dilma Rousseff announced that one million foreign tourists visited the country and three million Brazilian tourists travelled around the country during the event. Around 3.4 million people bought tickets to attend matches at the stadiums. Fan Fests attracted another five million people. By mid-June 2014, a total of 340,000 daily hotel bookings were recorded.

According to data released by Brazil Central Bank in July 2014, international visitors spent US$797 million in Brazil in the month of June 2014. Higher revenues from spending by international tourists in Brazil and reduced foreign trips by Brazilians during 2014 World Cup contributed in improvement of international travel account of services trade, which posted a deficit of US$1.2 billion in June 2014, down 17.3% from June 2013, providing some cushion to current account deficit. Economists believe that current account deficit over 5% of gross domestic product may lead to currency crisis in Brazil involving difficulty in debt repayments and currency depreciation. The twelve-month current account deficit remained stable at 3.6% of gross domestic product in June 2014, at the same level as in August 2013, because of narrowed gap in international travel account of services trade.

A survey conducted by Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV) and the Foundation Institute of Economic Research (FIPE), conducted by interviewing 6,627 foreign visitors and 6,038 Brazilians during the World Cup indicated that about a million tourists from 203 different countries came to Brazil during the tournament. Foreign visitors stayed in the country for an average of 13 days and visited 378 Brazilian municipalities. Thus, the event offered an opportunity for the country to promote its less popular tourist destinations to a group of diverse visitors. Furthermore, the survey suggests that 95% of the visitors expressed the desire to revisit, which might indicate brighter days for tourism industry in the future, provided that these tourists actually come back.

A Rocky Road to the Event

A look into World Cup-related investment across these sectors reveals that there have been mixed repercussions of the event across social and economy spheres. However, on a broader level, the planning, preparation, and organization of the event were challenged by a range of problems, which led to lost opportunities or even negative outcomes, and questioned the overall benefit of organizing 2014 World Cup by Brazil.

Increased Costs and Delays

In 2007, Carlos Langoni, then Finance Director of the 2014 World Cup Local Organizing Committee and former President of the Brazil Central Bank, estimated the World Cup-related cost at US$6 billion. In January 2010, Sports Ministry revised the estimates to around US$11 billion. According to the Responsibility Matrix 2013, the estimated actual expenditure was US$13 billion.

The increase in costs is believed to be partially attributed to the rampant political corruption in Brazil. By analyzing Brazil’s electoral data and government audit reports from 2007 to 2013, The Associated Press reported many-fold increase in campaign contributions to the political parties by the construction firms that were awarded most World Cup projects. This is suspected to have been a form of a bribe to win Word Cup-related projects and later allowed these companies to make huge profits by indulging into unfair practices such as fraudulent billing, under-compensation to workers, etc. For instance, Andrade Gutierrez, a construction conglomerate that got large contracts associated with World Cup, increased its political contributions to US$37.1 million in 2012 from US$73,180 in 2008. Adding to the suspicion of possible political linkage of the construction firms involved in World Cup-related projects, in 2014, Contas Abertas, a watchdog group that scrutinizes Brazilian government budgets, alleged that some contracts were awarded directly to the chosen construction firms and were never made available for public bid. A government audit report on construction projects associated with World Cup, released in early 2014, highlights several instances of price-gouging and suspected misuse of financial linkages between the construction firms and government. For instance, Brasilia’s government failed to impose US$16 million fine on Andrade Gutierrez for a five-month delay in completion of the stadium in the city. However, no corruption charges have been filed yet on individuals or companies related to World Cup work.

Additionally, experts believe that the lacking capability of construction firms in project planning and management also contributed to rising costs and delays. Furthermore, in order to accelerate the construction work, ‘emergency’ contracts were awarded at a higher price to leading (and known to be influential) construction firms, waiving the normal contracts, which further led to inflated costs.

Overexploitation of Workers

Construction projects, especially the stadiums, which were left to last-minute completion, had adverse effect on the workers. Many workers were assigned twelve-hour shifts and were asked to give up holidays to finish the construction work in time for World Cup. Some workers reportedly lost their employment as they could no longer tolerate the stress and physical strain. Around eight workers died in accidents on construction sites and these accidents occurred mainly due to lack of safety measures and inhuman working conditions. Many workers that had migrated from rural parts of the country to urban areas in search of World Cup-related employment opportunities complained about poor working and living conditions and under-compensation. Between 2007 and 2014, workers in various parts of the country, supported by labor unions, went on strike demanding their basic rights. Strikes and accidents triggered further delay in construction work related to World Cup.

Projects Financing and Funds Clearance Issues

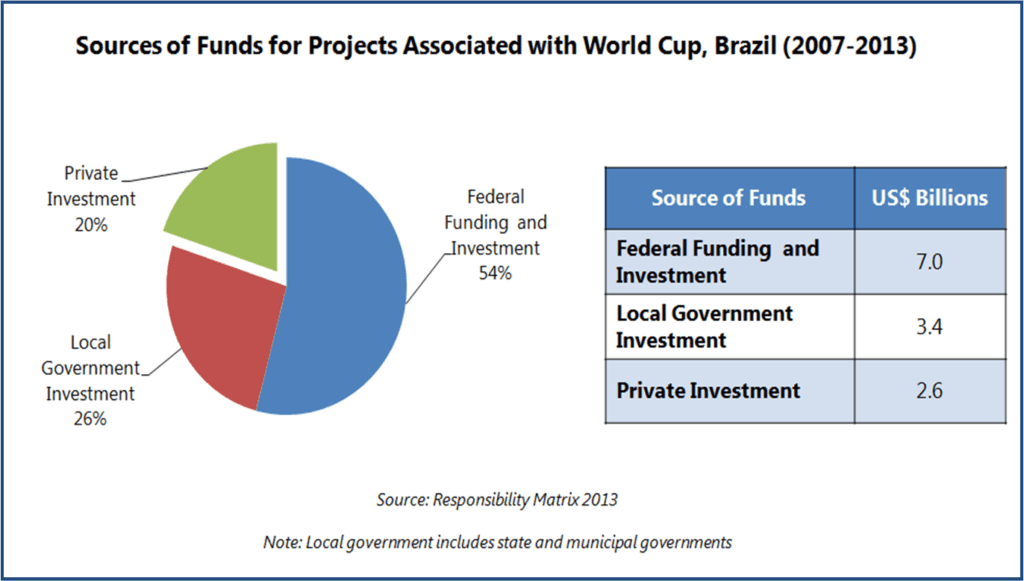

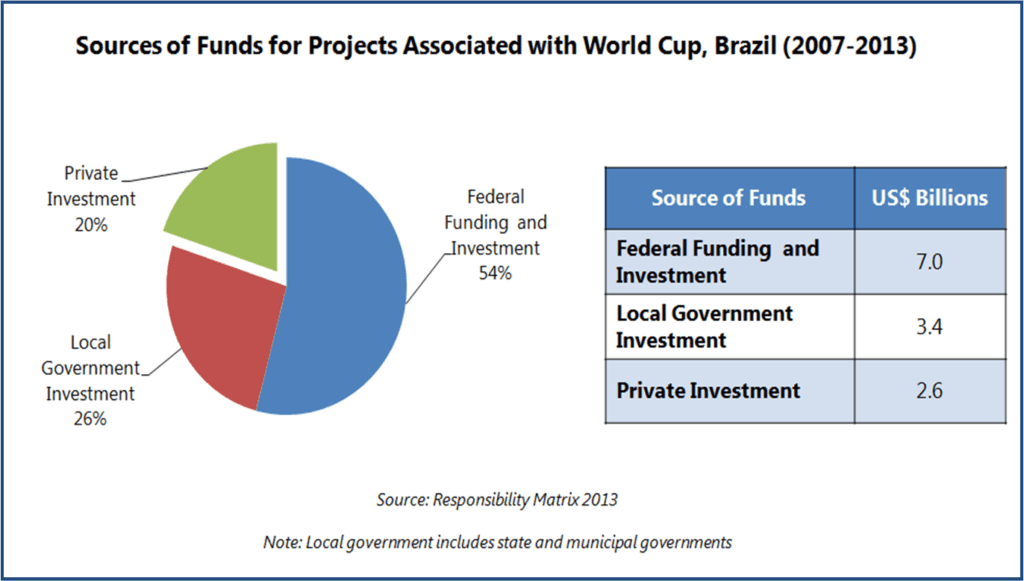

According to Responsibility Matrix 2013, 80% of the total investments in World Cup-related projects were financed through investments and funding from federal, state and municipal governments.

A larger role from the private sector was anticipated in preparation for 2014 World Cup, particularly for the event-specific projects such as construction of stadiums, and the government was expected to contribute mainly as a facilitator for the event. As the actual contribution from private funding was limited, the strain was passed on to local government budgets. In 2010, on failure to attract private investments for building stadiums for World Cup, the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES) opened a credit line of US$2.7 billion for completion of the World Cup stadiums. After receiving requests from states for financing, BNDES took up to three months to analyze the proposals and consequently the stadium construction work was further delayed.

Furthermore, complex and time consuming procedures continued to cause delay in funds clearing. According to World Cup Transparency Portal, by March 2014, 89.9% project work had already been contracted out, but payments were done for only 51.2% of them. This was implying increased payments out of local governments’ pockets in the second quarter of 2014, which occurred at the expense of several high-importance sectors such as healthcare or education.

Roadblocks for Micro and Small Enterprise

Around 44,000 enterprises associated with Brazilian Service of Support for Micro and Small Enterprises (SEBRAE), a non-profit autonomous institution promoting competitiveness and sustainable development of micro and small enterprises, are estimated to have earned US$230 million in revenue from World Cup-generated business opportunities from 2007 to 2014, which indicates that several of them were able to take good advantage of the opportunities provided by the event. However, it appears that many small food and FIFA merchandise vendors could have benefited to a greater extent, if they were not deterred to capitalize on large demand generated in the close proximity of stadiums during World Cup by FIFA’s heavy fee of US$8,000 from any non-FIFA approved vendor who wished to operate in a 1.5 km radius of host stadiums. The question is whether such a considerable fee remains in proportion to small and micro vendors’ scale of operations, who after all distribute FIFA merchandize, contributing to the publicity success of the event.

Even the few selected street vendors (estimated at around 1,000) that were granted temporary licenses to sell FIFA sponsors’ goods in the FIFA prohibited zones during the World Cup were not much at advantage. FIFA sponsors were responsible for selecting, contracting, and training the vendors. Proven experience of the vendors in selling goods in the neighborhood was the main the criteria for selection. Vendors were provided with uniforms, authorization cards, as well as goods to sell. Vendors retained a fixed 30% share in revenue from goods sold during the event, which limited their ability to negotiate the profit margins. As these vendors were not allowed to sell goods from non-FIFA sponsors, they lost an opportunity of earning higher revenues by selling locally manufactured or self-produced goods.

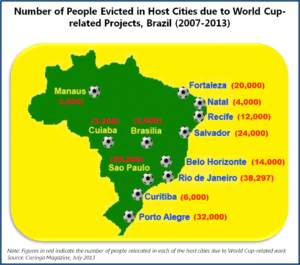

Mass Eviction

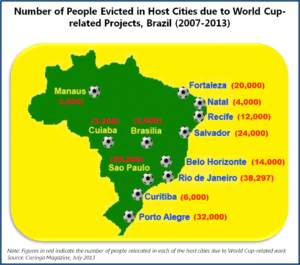

Between 2007 and 2013, about 248,297 people were forced to leave their homes due to infrastructure work for the tournament. Social activists claimed that most of the designated areas for relocation were at far distances from former dwellings and were less developed. There have been complaints that the compensations offered by the government to people for relocation were unfair and insufficient.

Between 2007 and 2013, about 248,297 people were forced to leave their homes due to infrastructure work for the tournament. Social activists claimed that most of the designated areas for relocation were at far distances from former dwellings and were less developed. There have been complaints that the compensations offered by the government to people for relocation were unfair and insufficient.

For instance, in May 2014, AlJazeera reported that in Rio de Janerio compensation sums offered to people for relocation was half the value of their old house, while employment opportunities in relocated areas remain scarce. These people belong to most impoverished communities in Brazil and lack of work opportunities and inadequate compensation may further worsen their condition, which may also lead to increase in crime rate.

Tax Revenue Lost Opportunity

Brazil government was rather generous in giving out tax breaks in relation to various activities associated with 2014 World Cup, and this was considerable revenue lost for the budget. In 2010, the Ministry of Treasury announced tax breaks for the construction and renovation of the stadiums for World Cup. The entities involved in stadium works were granted exemption from Industrialized Products Tax, Importation Tax, or social contributions. In addition, the twelve host cities were granted exemption from State Value Added Tax on all operations involving merchandise and materials for construction or renovation of the stadiums. Furthermore, all expenditure by FIFA in Brazil for World Cup was exempted from taxation. While it is always expected that tax relieve and exemptions are given in such high-profile, national events, it remains doubtful whether Brazil could afford foregoing such tax revenue, especially in the face of many social, structural, and welfare problems eating away the country’s public system.

EOS Perspective

2014 World Cup is believed to have provided a boost to Brazil economy, but this push was not significant enough to upswing economy’s recently sluggish growth. The temporary rise in tourism associated with the event, can, to some extent, offset lowered production and disruptions in the country during the event. However, it is unlikely that gains from this short tournament will make up for the inflated and overrun costs, suspected political corruption, fraudulently spent or lost money, missed opportunities of diverting some of the funds to other sectors, or social damage caused by disregard for dwellers and workers, along with other social costs that follow these deficiencies in a ripple effect. World Cup-generated opportunities benefited mostly construction, hospitality, travel, and tourism sectors.

The improvements and modernization of infrastructure will leave positive legacy for the country, which is a positive outcome, however achieved at a great expense, arguably not comparable with the country’s current financial capabilities. As emotions cool down and more objective analyses are offered by various experts, it is more and more visible that the positive impact of the event on Brazil economy, its people, and businesses is rather short-lived. Over long term, it is likely that Brazil will end up being the loser of the 2014 FIFA World Cup. As the event-generated income sources slowly dry up, Brazil will be left with a huge bill to pay in its hand, one that will have to be settled over years to come.

In addition to government policies, FDI has played a key role in nurturing the non-oil sector. Nigeria has experienced a compounded annual growth of 20% in the number of Greenfield FDI projects from 2007 to 2013; 50% (total number of projects being 306) of these projects were service-oriented. The telecom sector particularly witnessed strong growth by attracting 24% of all FDI projects, while coal, oil, and natural gas received only 8% of foreign direct investment during 2007-2013.

In addition to government policies, FDI has played a key role in nurturing the non-oil sector. Nigeria has experienced a compounded annual growth of 20% in the number of Greenfield FDI projects from 2007 to 2013; 50% (total number of projects being 306) of these projects were service-oriented. The telecom sector particularly witnessed strong growth by attracting 24% of all FDI projects, while coal, oil, and natural gas received only 8% of foreign direct investment during 2007-2013.

Between 2007 and 2013, about 248,297 people were forced to leave their homes due to infrastructure work for the tournament. Social activists claimed that most of the designated areas for relocation were at far distances from former dwellings and were less developed. There have been complaints that the compensations offered by the government to people for relocation were unfair and insufficient.

Between 2007 and 2013, about 248,297 people were forced to leave their homes due to infrastructure work for the tournament. Social activists claimed that most of the designated areas for relocation were at far distances from former dwellings and were less developed. There have been complaints that the compensations offered by the government to people for relocation were unfair and insufficient.