The growing paucity of radiologists across the globe is alarming. The availability of radiologists is extremely disproportionate globally. To illustrate this, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, USA, had 126 radiologists, while the entire country of Liberia had two radiologists, and 14 countries in the African continent did not have a single radiologist, as of 2015. This leads to a crucial question – how to address this global unmet demand for radiologists and diagnostic professionals?

Increasing capital investment signals rising interest in AI in healthcare diagnostics

The global market for Artificial Intelligence (AI) in healthcare diagnostics is forecast to grow at a CAGR of 8.3%, from US$513.3 million in 2019 to US$825.9 million in 2025, according to Frost & Sullivan’s report from 2021. This growth in the healthcare diagnostics AI market is attributed to the increased demand for diagnostic tests due to the rising prevalence of novel diseases and fast-track approvals from regulatory authorities to use AI-powered technologies for preliminary diagnosis.

Imaging Diagnostics, also known as Medical Imaging is one of the key areas of healthcare diagnostics that is most interesting in exploring AI implementation. From 2013 to 2018, over 70 firms in the imaging diagnostics AI sector secured equity funding spanning 119 investment deals and have progressed towards commercial beginnings, thanks to quick approvals from respective regulatory bodies.

Between 2015 and 2021, US$3.5 billion was secured by AI-enabled imaging diagnostics firms (specialized in developing AI-powered solutions) globally for 290 investment deals, as per Signify Research. More than 200 firms (specialized in developing AI-powered solutions) globally were building AI-based solutions for imaging diagnostics, between 2015 and 2021.

The value of global investments in imaging diagnostics AI in 2020 was approximately 8.8% of the global investments in healthcare AI. The corresponding figure in 2019 was 10.2%. The sector is seeing considerable investment at a global level, with Asia-based firms (specialized in developing AI-powered solutions) having secured around US$1.5 billion, Americas-based companies raising US$1.2 billion, and EMEA-based firms securing over US$600 million between 2015 and 2021.

As per a survey conducted by the American College of Radiology in 2020 involving 1,427 US-based radiologists, 30% of respondents said that they used AI in some form in their clinical practice. This might seem like a meager adoption rate of AI amongst US radiologists. However, considering that five years earlier, there were hardly any radiologists in the USA using AI in their clinical practice, the figure illustrates a considerable surge in AI adoption here.

However, the adoption of AI in healthcare diagnostics is faced with several challenges such as high implementation costs, lack of high-quality diagnostic data, data privacy issues, patient safety, cybersecurity concerns, fear of job replacement, and trust issues. The question that remains is whether these challenges are considerable enough to hinder the widespread implementation of AI in healthcare diagnostics.

AI advantages help answer the needs in healthcare diagnostics

Several advantages such as improved correctness in disease detection and diagnosis, reduced scope of medical and diagnosis errors, improved access to diagnosis in areas where radiologists are unavailable, and increased workflow and efficacy drive the surge in the demand for AI-powered solutions in healthcare diagnostics.

One of the biggest benefits of AI in healthcare diagnostics is improved correctness in disease detection and diagnosis. According to a 2017 study conducted by two radiologists from the Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, AI could detect lesions caused by tuberculosis in chest X-rays with an accuracy rate of 96%. Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts uses AI to scan images and detect blood diseases with a 95% accuracy rate. There are numerous similar pieces of evidence supporting the AI’s ability to offer improved levels of correctness in disease detection and diagnosis.

A major benefit offered by AI in healthcare diagnostics is the reduced scope of medical and diagnosis errors. Medical and diagnosis errors are among the top 10 causes of death globally, according to WHO. Taking this into consideration, minimizing medical errors with the help of AI is one of the most promising benefits of diagnostics AI. AI is capable of cutting medical and diagnosis errors by 30% to 40% (trimming down the treatment costs by 50%), according to Frost & Sullivan’s report from 2016. With the implementation of AI, diagnostic errors can be reduced by 50% in the next five years starting from 2021, according to Suchi Saria, Founder and CEO, Bayesian Health and Director, Machine Learning and Healthcare Lab, Johns Hopkins University.

Another benefit that has been noticed is improved access to diagnosis in areas where there is a shortage of radiologists and other diagnostic professionals. The paucity of radiologists is a global trend. To cite a few examples, there is one radiologist for: 31,707 people in Mexico (2017), 14,634 people in Japan (2012), 130,000 people in India (2014), 6,827 people in the USA (2021), 15,665 people in the UK (2020).

AI has the ability to modify the way radiologists operate. It could change their active approach toward diagnosis to a proactive approach. To elucidate this, instead of just examining the particular condition for which the patient requested medical intervention, AI is likely to enable radiologists to find other conditions that remain undiagnosed or even conditions the patient is unaware of. In a post-COVID-19 era, AI is likely to reduce the backlogs in low-emergency situations. Thus, the technology can help bridge the gap created due to radiologist shortage and improve the access to diagnosis of patients to a drastic extent.

Further, AI helps in improving the workflow and efficacy of healthcare diagnostic processes. On average at any point in time, more than 300,000 medical images are waiting to be read by a radiologist in the UK for more than 30 days. The use of AI will enable radiologists to focus on identifying dangerous conditions rather than spend more time verifying non-disease conditions. Thus, the use of AI will help minimize such delays in anomaly detection in medical images and improve workflow and efficacy levels. To illustrate this, an AI algorithm named CheXNeXt, developed in a Stanford University study in 2018 could read chest X-rays for 14 distinct pathologies. Not only could the algorithm achieve the same level of precision as the radiologists, but it could also read the images in less than two minutes while the radiologists could read them in an average of four hours.

Black-box AI: A source of challenges to AI implementation in healthcare diagnostics

The black-box nature of AI means that with most AI-powered tools, only the input and output are visible but the innards between them are not visible or knowable. The root cause of many challenges for AI implementation in healthcare diagnostics is AI’s innate character of the black box.

One of the primary impediments is tracking and evaluating the decision-making process of the AI system in case of a negative result or outcome of AI algorithms. That is to say, it is not possible to detect the fundamental cause of the negative outcome within the AI system because of the black-box nature of AI. Therefore, it becomes difficult to avoid such occurrences of negative outcomes in the future.

The second encumbrance caused by the black-box nature of AI is the trust issues of clinicians that are hesitant to use AI applications because they do not completely comprehend the technology. Patients are also expected to not have faith in the AI tools because they are less forgiving of machine errors as opposed to human errors.

Further, several financial, technological, and psychological challenges while implementing AI in healthcare diagnostics are also associated with the black-box nature of the technology.

Financial challenges

High implementation costs

According to a 2020 survey conducted by Definitive Healthcare, a leading player in healthcare commercial intelligence, cost continues to be the most prominent encumbrance in AI implementation in diagnostics. Approximately 55% of the respondents who do not use AI pointed out that cost is the biggest challenge in AI implementation.

The cost of a bespoke AI system can be between US$20,000 to US$1 million, as per Analytics Insights, while the cost of the minimum viable product (a product with sufficient features to lure early adopters and verify a product idea ahead of time in the product development cycle) can be between US$8,000 and US$15,000. Other factors that also decide the total cost of AI are the costs of hiring and training skilled labor. The cost of data scientists and engineers ranges from US$550 to US$1,100 per day depending on their skills and experience levels, while the cost of a software engineer (to develop applications, dashboards, etc.) ranges between US$600 and US$1,500 per day.

It can be gauged from these figures that the total cost of AI implementation is high enough for the stakeholders to ponder upon the decision of whether to adopt the technology, especially if they are not fully aware of the benefits it might bring and if they are working with ongoing budget constraints, not infrequent in healthcare institutions.

Technological challenges

Overall paucity of availability of high-quality diagnostic data

High-quality diagnostic and medical datasets are a prerequisite for the testing of AI models. Because of the highly disintegrated nature of medical and diagnostic data, it becomes extremely difficult for data scientists to procure the data for testing AI algorithms. To put it in simple terms, patient records and diagnostic images are fragmented across myriad electronic health records (EHRs) and software platforms which makes it hard for the AI developer to use the data.

Data privacy concerns

AI developers must be open about the quality of the data used and any limitations of the software being employed, without risking cybersecurity and without breaching intellectual property concerns. Large-scale implementation of AI will lead to higher vulnerability of the existing cloud or on-premise infrastructure to both physical and cyber attacks leading to security breaches of critical healthcare diagnostic information. Targets in this space such as diagnostic tools and medical devices can be compromised by malware or software viruses. Compromised data and algorithms will result in errors in diagnosis and consequently inaccurate recommendations of treatment thereby causing stakeholders to refrain from using AI in healthcare diagnostics.

Patient safety

One of the foremost challenges for AI in healthcare diagnostics is patient safety. To achieve better patient safety, developers of AI algorithms must ensure the credibility, rationality, and transparency of the underlying datasets. Patient safety depends on the performance of AI which in turn depends on the quality of the training data. The better the quality of the data, the better will be the performance of the AI algorithms resulting in higher patient safety.

Mental and psychological challenges

Fear of job substitution

A survey published in March 2021 by European Radiology, the official journal of the European Society of Radiology, involving 1,041 respondents (83% of them were based in European countries) found that 38% of residents and radiologists are worried about their jobs being cut by AI. However, 48% of the respondents were more enterprising and unbiased towards AI. The fear of substitution could be attributed to the fact that those having restricted knowledge of AI are not completely educated about its shortcomings and consider their skillset to be less up-to-date than the technology. Because of this lack of awareness, they fail to realize that radiologists are instrumental in developing, testing, and implementing AI into clinical practice.

Trust issues

Trusting AI systems is crucial for the profitable implementation of AI into diagnostic practice. It is of foremost importance that the patient is made aware of the data processing and open dialogues must be encouraged to foster trust. Openness or transparency that forges confidence and reliability among patients and clinicians is instrumental in the success of AI in clinical practice.

EOS Perspective

With trust in AI amongst clinicians and patients, its adoption in healthcare diagnostics can be achieved at a more rapid pace. Lack of it breeds fear of job replacement by the technology amongst clinicians. Further, scarcity of awareness of AI’s true potential as well as its limitations also threatens diagnostic professionals from getting replaced by the technology. Therefore, to fully understand the capabilities of AI in healthcare diagnostics, clinicians and patients must learn about and trust the technology.

With the multitude and variety of challenges for AI implementation in healthcare diagnostics, its importance in technology becomes all the more critical. The benefits of AI are likely to accelerate the pace of adoption and thereby realize the true potential of AI in terms of saving clinicians’ time by streamlining how they operate, improving diagnosis, minimizing errors, maximizing efficacy, reducing redundancies, and delivering reliable diagnostic results. To power healthcare diagnostics with AI, it is important to view AI as an opportunity rather than a threat. This in turn will set AI in diagnostics on its path from pipe dream to reality.

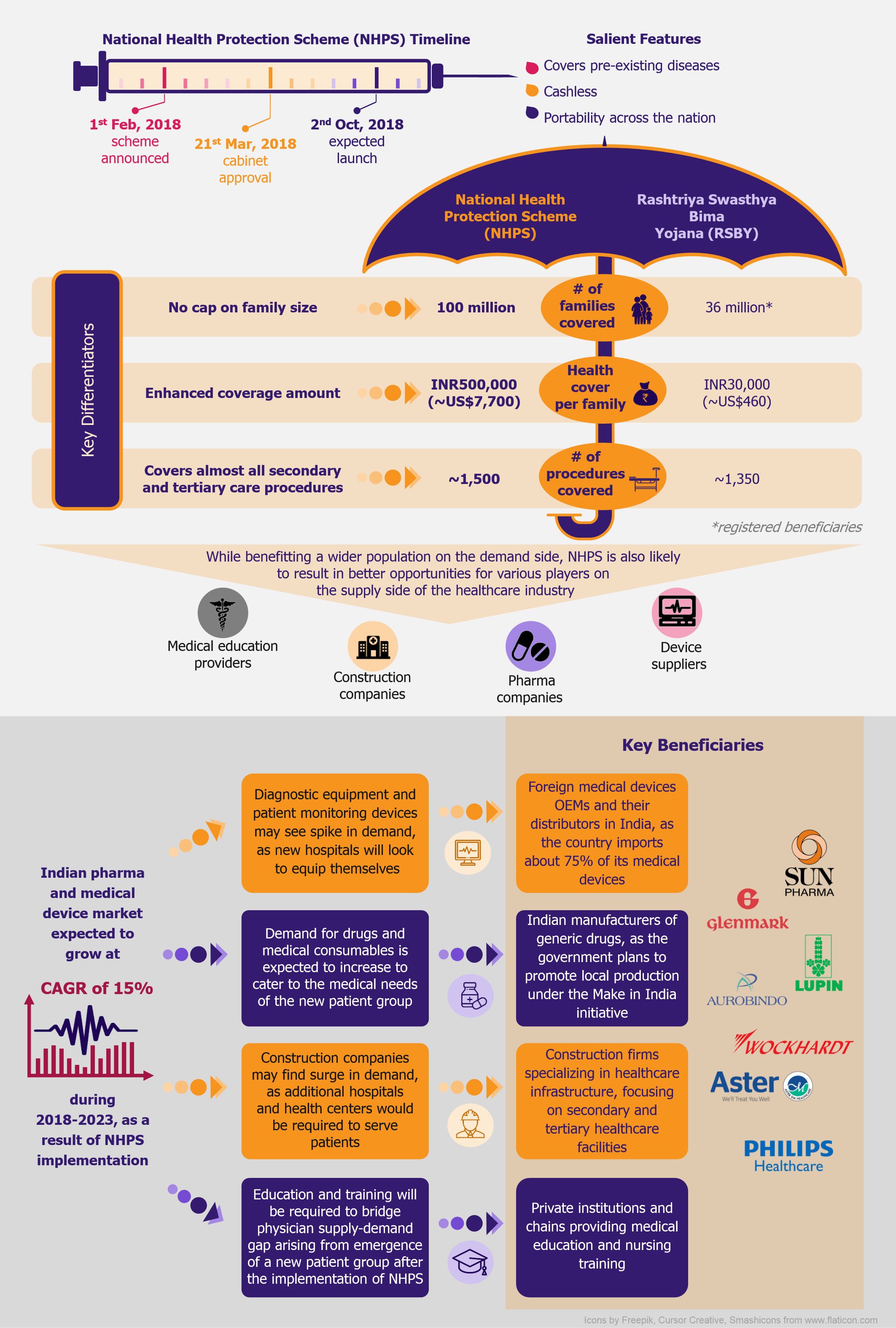

NHPS is expected to provide secondary and tertiary healthcare access to more than 40% of the Indian population, which was earlier deprived of it due to financial constraints. This will create a new healthcare market, giving boost to the entire healthcare ecosystem in India. Companies across the entire healthcare value chain, including medical education providers, healthcare service providers, construction firms, pharmaceutical and medical devices companies, etc., are expected to witness ample growth opportunities. One can expect increased investments in the Indian healthcare sector by private companies as well as foreign investors.

NHPS is expected to provide secondary and tertiary healthcare access to more than 40% of the Indian population, which was earlier deprived of it due to financial constraints. This will create a new healthcare market, giving boost to the entire healthcare ecosystem in India. Companies across the entire healthcare value chain, including medical education providers, healthcare service providers, construction firms, pharmaceutical and medical devices companies, etc., are expected to witness ample growth opportunities. One can expect increased investments in the Indian healthcare sector by private companies as well as foreign investors.