1.5kviews

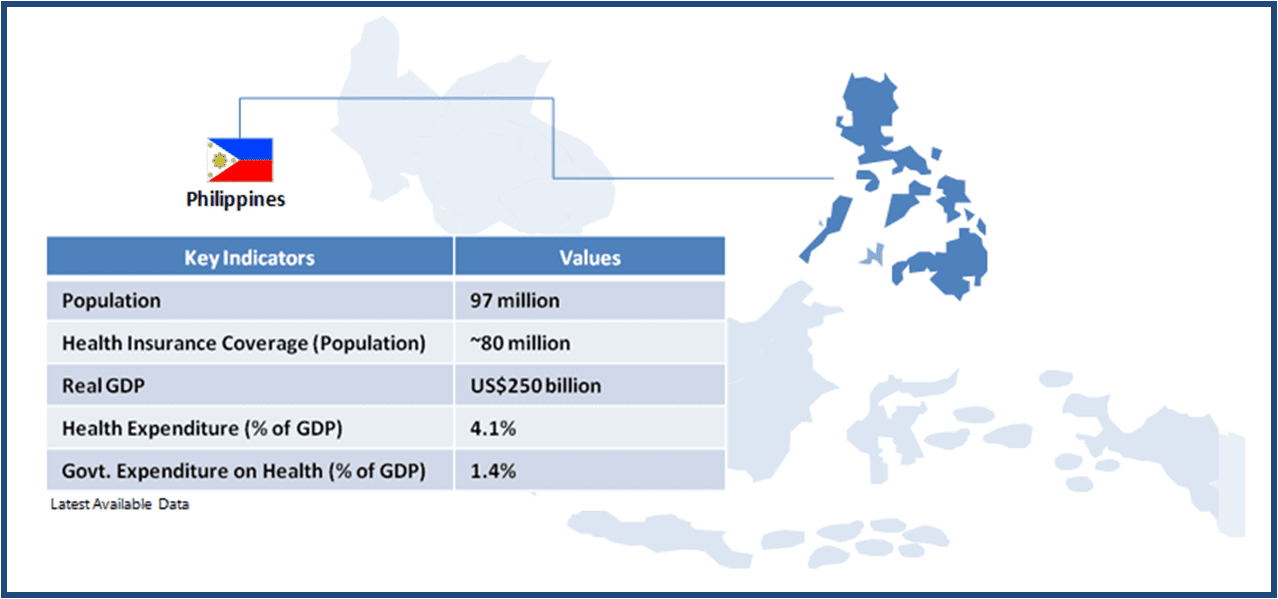

Over the years, governments across emerging markets have realised how critical universal healthcare coverage is for their population. While some countries have taken the challenge head-on, others have followed a wait-and-watch policy to see how such systems are being implemented, and gradually adopted a system that is based on the good practices of several healthcare plans.

In recent years, several Southeast Asian countries have adopted different forms of universal healthcare plans for their countries. Universal healthcare-related policies and delivery mechanisms were largely based on existing healthcare systems, a result of gradual development (based on local factors and priorities). Therefore, while theoretically universal healthcare exists (wherever applicable), it differs in terms of the actual benefits (e.g. quality and range of services and monetary advantage to patients).

We review these plans across a few Southeast Asian countries, to understand their infrastructure and design, and available opportunities for healthcare service providers, medical device manufacturers and pharmaceuticals companies. As part of this series, we start with Philippines, where about 80% of the population is currently covered under the universal healthcare plan, called PhilHealth.

This article is part of a series focusing on universal healthcare plans across selected Southeast Asian countries. The series also includes a look into the plans in The Philippines, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand.

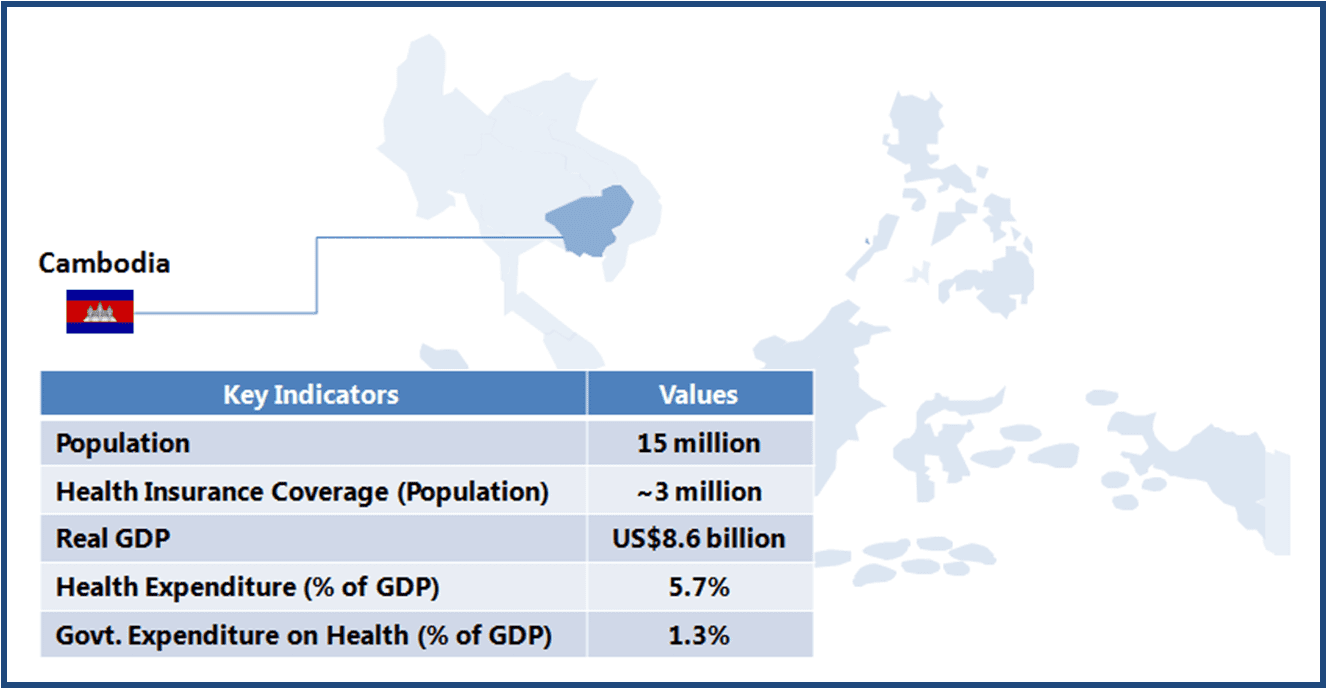

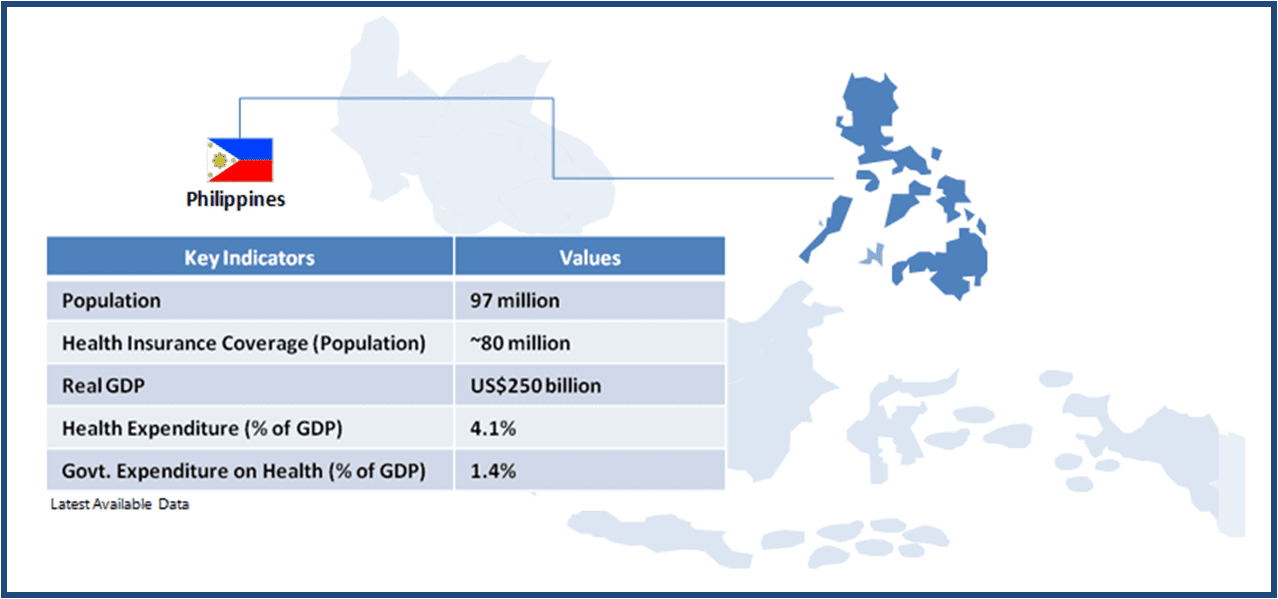

The Philippines is a lower-middle income country with a population of about 97 million. In spite of a strong focus on healthcare services, inequality in terms of healthcare access to various socio-economic groups and regions remains a persistent issue. Achieving universal healthcare access for all its citizens is a key objective of the government’s National Objectives for Health (2011-2016) program, and the government aims to fulfil three primary goals through this program – 1) financial risk protection; 2) better health outcome; 3) responsive healthcare system.

The first step towards universal healthcare was the launch of Medicare (1969), which provided health insurance to formal sector (public and private) employees. Coverage was extended to the poorer section of the population and the informal sector with the creation of PhilHealth (Medicare was merged with it) in 1995.

As of 2013, more than 80% of the country’s population was covered under the national health insurance program PhilHealth. The government aims to provide 100% coverage by 2016.

For a private sector healthcare player (pharmaceutical company, medical device manufacturer, or healthcare service provider), a country with 100% insured population presents strong incentives in form of greater access to diverse sections of the population with varied service and product needs, which will inevitably drive sales. However, to maintain the effectiveness of universal healthcare coverage, the government needs to work beyond simply the numerical (on paper) coverage of its population under the health cover to ensuring informal sector participation in the scheme, consistency in service delivery at primary care level, and adequate coverage of diseases.

The long-term success of social health insurance (and related with it, the prospects for healthcare sector stakeholders) will be determined primarily by how PhilHealth has been designed and what emphasis is being laid on infrastructure.

We take a closer look at these two critical aspects of the universal healthcare program.

| INFRASTRUCTURE |

| Key Stakeholders |

- The Department of Health (DOH) is responsible for developing programs and policies, monitoring standards, and provision of specialized and tertiary level care

- DOH is represented at the regional level by centres for health and development (CHD), which link national programs with local government units (LGU); provincial administration (including hospitals and primary care) fall under each LGU

- LGU administers healthcare services through Health Boards at the provincial (led by the governor), city (led by the mayor), and municipal (led by municipal mayor) levels

- Barangay (village) is the smallest administrative unit with primary health station/health centre

|

| Healthcare Service Delivery |

- Public hospitals account for about 40% of approximately 1,800 hospitals in the Philippines

- Based on the range and quality of services offered, hospitals are classified into four levels:

- Level 1: general hospital with maternity ward, dental clinics, 1st level X-ray, secondary clinical laboratory with consulting pathologist and blood station, and pharmacy

- Level 2: Level 1 facilities + respiratory units, ICU, NICU, HRPU, tertiary clinical laboratory, and 2nd level X-ray facility

- Level 3: Level 2 facilities + plus teaching/training, physical medicine and rehabilitation, ambulatory surgery, dialysis, tertiary laboratory, blood bank, and 3rd level X-ray

- Level 4: Specialty hospitals with treatment facilities for health conditions such as bones, heart, lungs, etc.

- Current hospital infrastructure:

- Level 1: ~ 352

- Level 2: ~ 276

- Level 3: ~ 41

- Level 4: ~ 51

- Private Hospitals: ~ 1,120

|

|

| KEY CHALLENGES |

Overlaps in the referral system

- Despite a highly decentralized healthcare delivery system, there are overlaps in the referral system in which district hospitals also act as the entry point into the country’s healthcare system. This may result in overcrowding of district hospitals, under-utilization of primary care centres, and loss of efficiency (patients being referred back to their local villages)

Variance in quality of healthcare service delivery

- Provision and quality of services largely depend on the LGU administration, where local funding plays a crucial role. Healthcare is one of several areas that fall under the administrative regime of an LGU; it has been observed that healthcare prioritization varies by LGU, implying that the quality of healthcare service delivery by LGU, leading to variance in service levels across the country

|

| DESIGN |

| Beneficiary Classification |

- PhilHealth members are classified into four groups

- Group 1: Formal sector employees

- Group 2: Self-employed professionals, members of the agricultural sector, and members of the informal sector

- Group 3: Retirees and pensioners who are at least 60 years old and have made 120 monthly contributions to PhilHealth

- Group 4: Poorest segment, belonging to the lowest 25% of the Philippine population and families listed in the National Household Targeting System for Poverty Reduction (NHTS-PR)

|

| Healthcare Insurance Financing |

- PhilHealth is mainly funded through government taxation, and employer and employee contribution

- Premium is fixed at 2.5% for formal sector employees (Group 1)

- Group 2 members fall under the individual paying program – those with less than P 25,000 monthly income pay P 2,400 as yearly premium, and those with over P 25,000 cut-off pay P 3,600 annually

- Group 3 and 4 are not required to pay any premium

|

| Payment System |

- Hospitals work under fee-for-service system, and are paid by PhilHealth for a defined set of services; reimbursements are paid directly to service providers

- DOH has identified 25 health conditions under case-payment (covers total cost per case) for PhilHealth cardholders

|

| Benefits |

- A defined set of services at pre-determined rates are covered by the PhilHealth scheme, and patients are required to pay out-of-pocket beyond the rate ceiling; coverage includes cost of medicines, supplies, and diagnostics during hospitalisation

- Outpatient consultations are not covered under PhilHealth; only a handful of health conditions, such as asthma, gastroenteritis, upper respiratory tract infection, and pneumonia qualify for treatment under the insurance plan

|

| Co-payment (Reimbursement) System |

- The PhilHealth system does not work on the principle of fixed-percentage co-payment system; patients (irrespective of the beneficiary group it belongs to) are required to pay the balance if the cost-of-service goes beyond a pre-determined ceiling for a particular service

- Ceiling rates may vary for the same service; higher ceiling rates are applicable for patients visiting specialty level hospital facilities

- For the 25 health conditions under the case-payment system, baseline benefits can range from 50% to 100%; DOH is also implementing a zero co-payment policy for beneficiaries under the sponsored program (Group 4 beneficiaries) for the 25 disease defined under case payment

|

| Reimbursement System for Drugs |

- Drugs, listed in the Philippine National Drugs Formulary, and required during hospitalisation are covered under PhilHealth; minimum ceiling rates (for single confinement period) for medicines according to the hospital level are the following:

- Level 1: P2,700

- Level 2: P3,360

- Level 3: P4,200

|

|

| KEY CHALLENGES |

Enrolment and recognition of actual beneficiaries by group

- Enrolment of population representing the informal sector into PhilHealth is a challenge, as due to their irregular income levels, beneficiaries under this category do not enrol or pay the mandated premium

- Also, identification of the poorest segment of the population, forming the sponsored category, is a grey area as the system is unable to ensure clear distinction between the entitled population versus those from other groups

Inadequate monitoring of service delivery

- PhilHealth mainly provides in-patient benefit with low financial protection due to the ceiling system

- Due to apparent lack of check on the fees charged by hospitals, even higher ceilings do not benefit patients, as hospitals raise their cost of services; consequently, the actual number of people availing its services appears to be significantly low

- For instance, in 2011, PhilHealth’s share in the country’s total healthcare expenditure was only 9.1% vis-à-vis out-of-pocket share at 52.7%; the rest 38% was government’s expenditure on healthcare other than PhilHealth

|

Opportunities for Healthcare Companies

Healthcare Service Providers

-

Significant Public Private Partnership (PPP) opportunities in exist in Philippines’ healthcare sector, to raise the level of services and to extend the coverage

-

Currently, only a 700-bed orthopaedic centre is being operated under the PPP model, and according to Philippine’s Health Secretary, there is significant opportunity for the PPP model in all DOH managed hospitals

-

The only roadblock for the adoption of PPP model is the perception of it being a move towards privatization of healthcare services (given that private sector already dominates the healthcare space in Philippines)

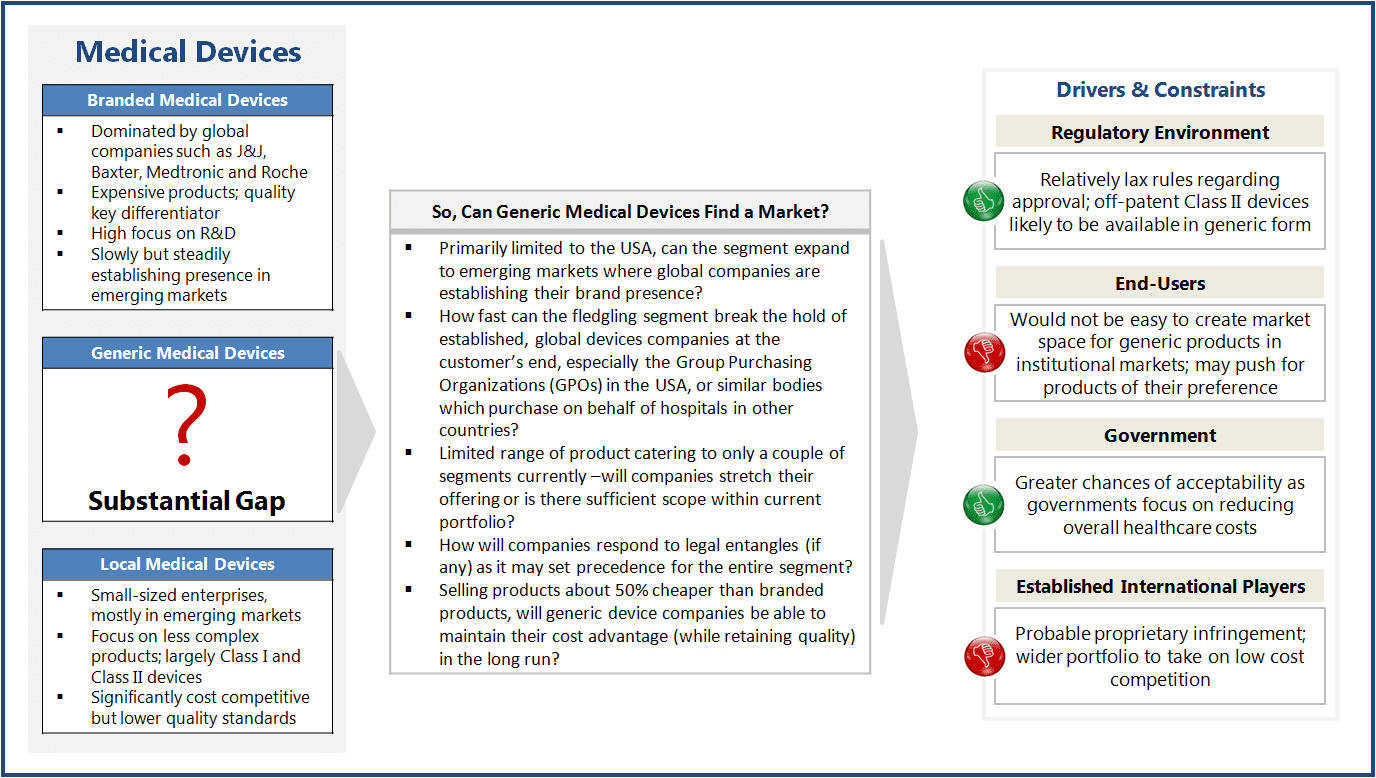

Medical Device Manufacturers

-

Public hospitals (especially those under LGU administration) usually are short of resources for the procurement of medical devices (mostly imported), which constraints them in providing patients with critical diagnostic services; this remains an area of concern as available devices will be inadequate to meet the 100% population coverage target of PhilHealth

-

At the same time, the demand for devices remains robust, and growth is expected on account of increase in the number of people under coverage as well as greater availability of healthcare services across the country. In order to further boost demand, medical device companies could explore ways to finance the purchase, so as to motivate hospitals to purchase equipment

-

The DOH has also hinted that critical equipment, such as CT scans and MRI machines, can be procured under a PPP model, providing an alternative option for device manufacturers to widen their presence

Pharmaceuticals Companies

-

In the current scenario, scope for pharmaceuticals companies is limited to medicines used for inpatient treatment. Sales potential is likely to increase as the government introduces zero co-payment policy for 25 health conditions for the sponsored category beneficiaries

-

Also, with the proposed widening of treatment coverage to include conditions such as hypertension and diabetes (was expected to come into effect in October 2013) which affect about 20% of the adult population, sales prospects is likely to improve

A Final Word

Philippines’ universal healthcare plan, PhilHealth, provides a strong foundation for access and quality enhancement of healthcare services to its population. With coverage of about 80% of its population currently, the country’s healthcare policy has tried to provide equality of service delivery to its citizens, and covers a range of common diseases and inpatient treatments. While there are obvious concerns around inadequate hospital facilities and diagnostics equipment, issues with accurate entitlement of benefits and inadequate monitoring of service delivery, the country’s healthcare administration is working with private partners to strengthen the system and focus on providing quality healthcare to its citizens.

From the perspective of healthcare industry participants, hospital services companies perhaps have a higher potential for growth in view of the shortage of hospital facilities across the country, while drugs companies must continue to rely on limited access to inpatient treatment facilities, providing drugs for the most common diseases (perhaps, also the cheaper product variants of their portfolio).