973views

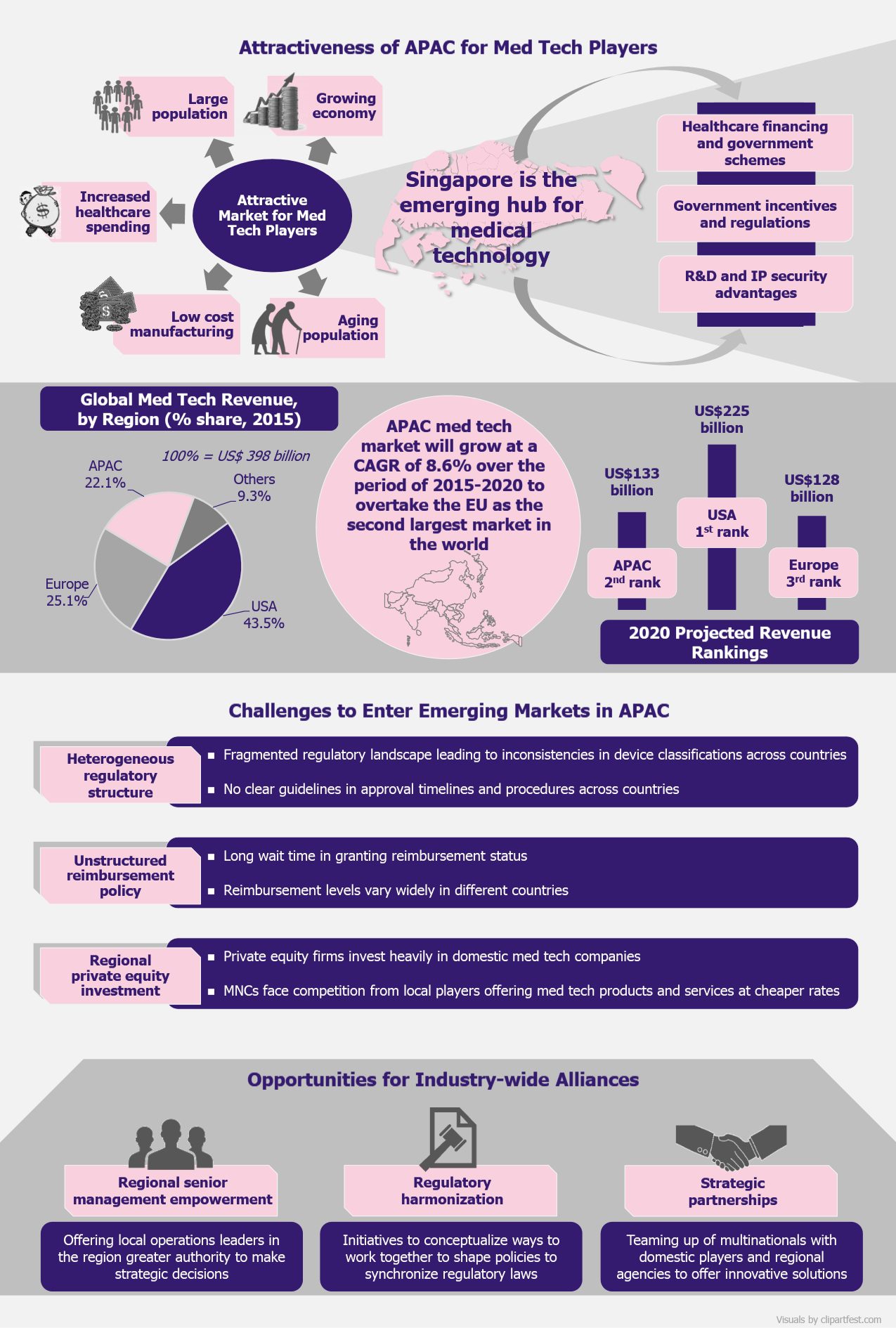

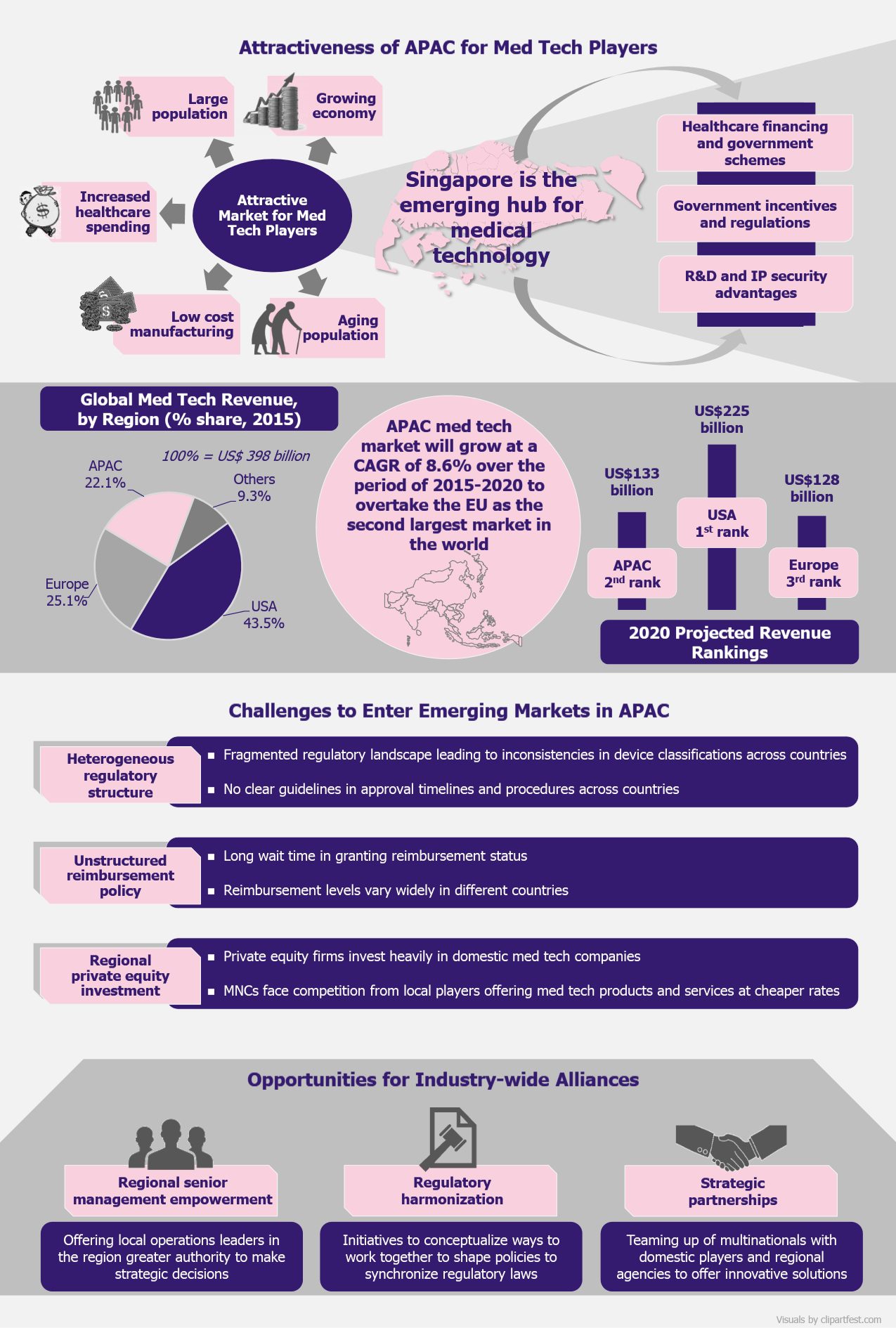

Being the third largest medtech market in the world, Asia-Pacific (APAC) is becoming an investment hub for medical technology companies globally. Owing to the economic growth of the region and increasing income of the local population, healthcare affordability and quality are on the rise. These are the ground reasons that drive medtech companies to focus on APAC for growth and business expansion. But having access to many local markets in this vast and diverse region seems a hard nut to crack for the medical device businesses. Singapore, with its favorable business environment, which vigorously defends intellectual property rights, currently seems to be the geography being eyed by major medtech companies. Though Singapore is well-positioned as a gateway to region’s medtech sector, entering other markets in the region is still challenging. With differences in the regulatory frameworks bundled with lack of clear reimbursement strategies, medtech companies find it strenuous to meet the requirements of the regional markets. In order to witness growth, it is imperative for medtech companies to focus on the growing opportunities for industry-wide collaboration, intending to create strong platforms for growth in APAC.

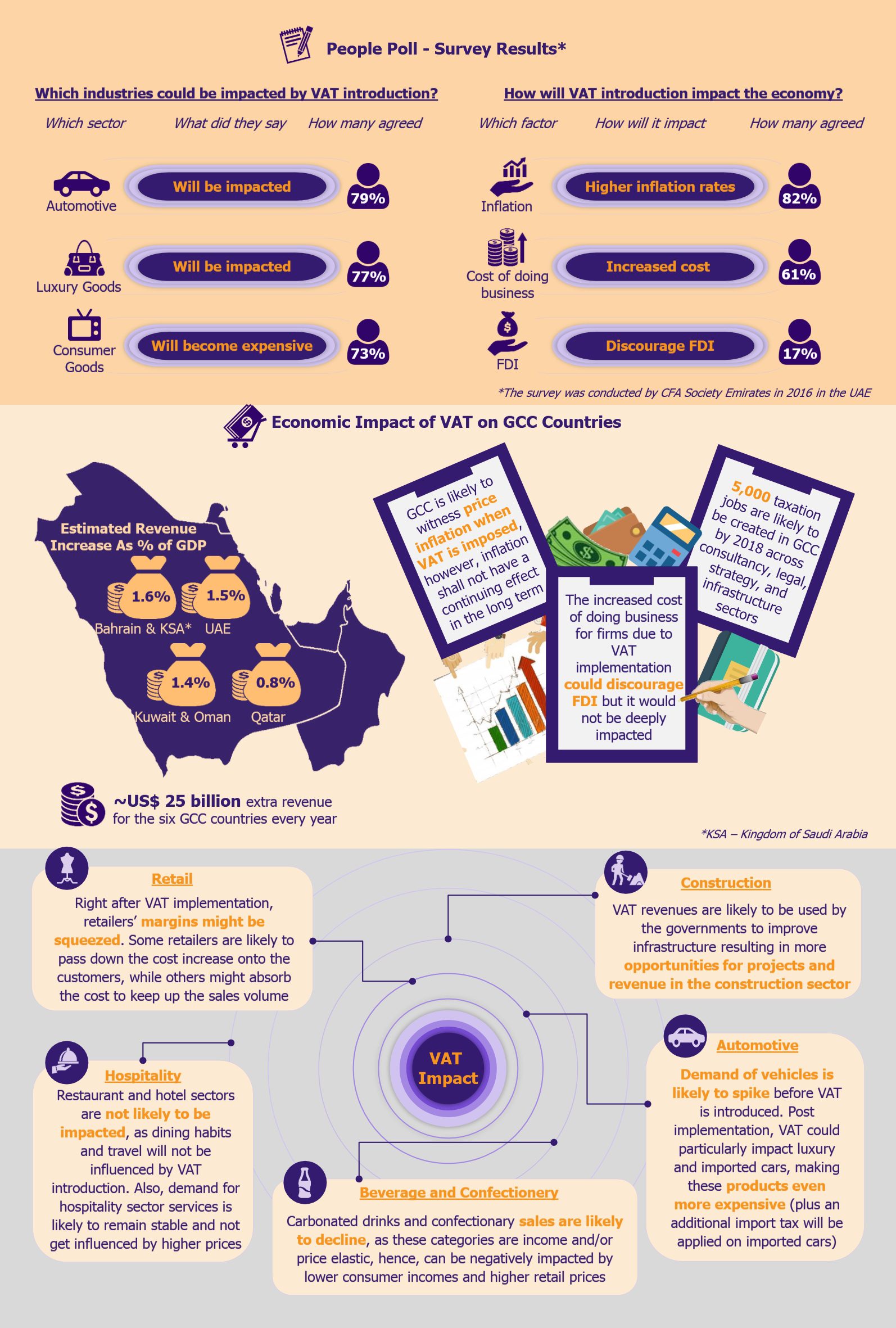

In 2015, APAC was the third largest medtech market in the world, after the USA and EU, accounting for over 22% of the global revenue which stood at US$398 billion. The region’s medtech industry is expected to be one of the fastest growing globally and is forecast to surpass EU by 2020 to become the second largest market behind the USA.

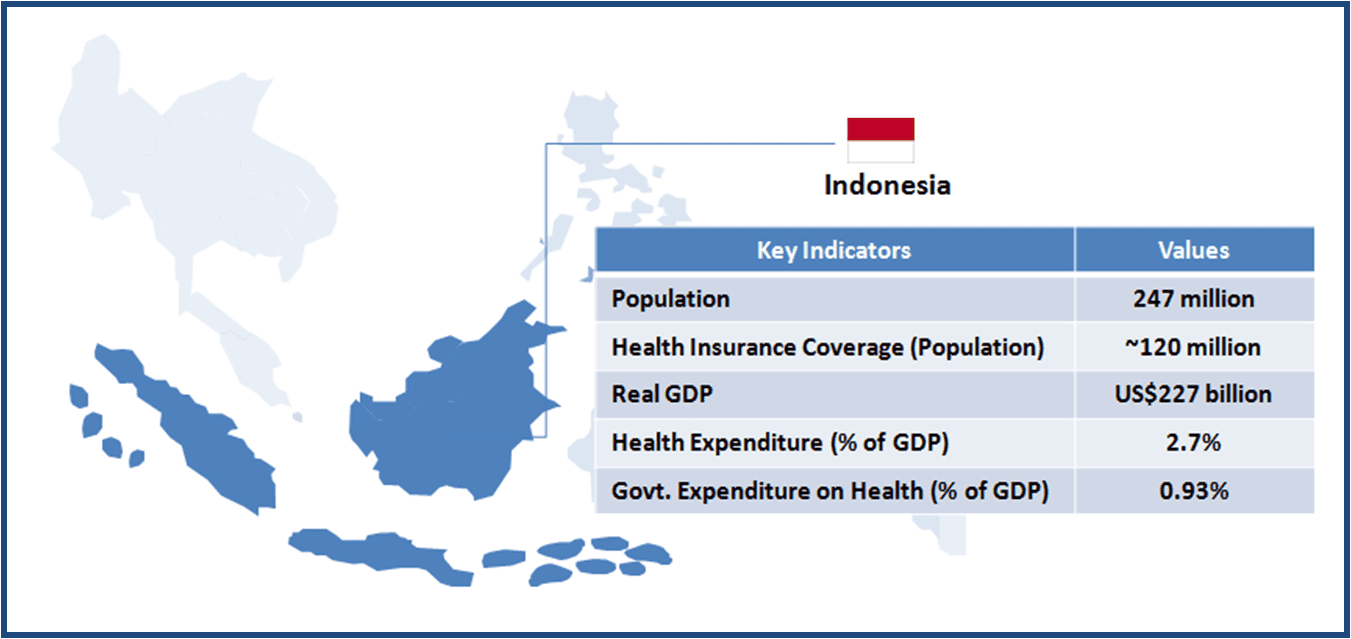

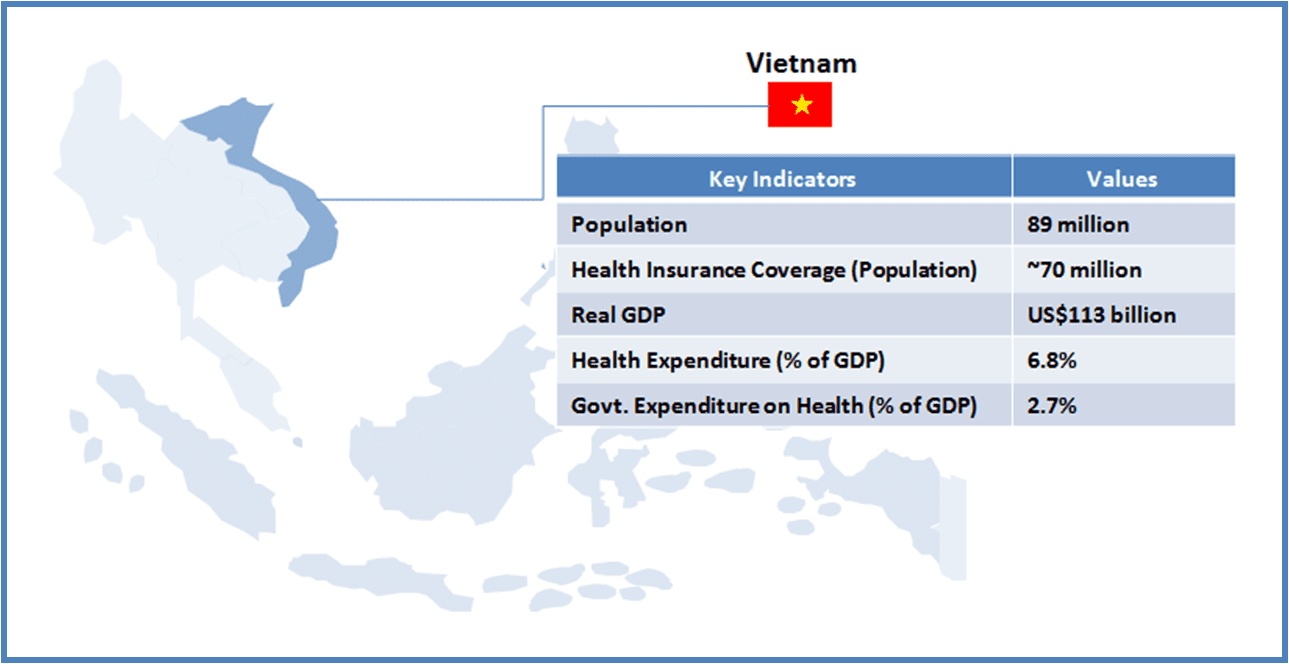

The high potential of APAC is fueled by the highly populated south-east Asian countries (China and India, the world’s two most populous countries, have a combined population of 2.8 billion), aging population (by 2050, Asia population will constitute 25% of the world’s elderly aged 60+), strong economic growth, increased spending power of the middle class, and reduced costs by manufacturing medical devices in the region rather than importing. The medtech revenue generated in the region was US$88 billion in 2015, expected to reach US$133 billion by 2020, achieving a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.6% over the period of five years.

Companies want to seize APAC’s potential for rapid development of medical devices by investing in the right geography that would support their expansion plans. One such location that offers the right environment for medical device players to grow is Singapore. In Asia, Singapore is the innovation center for medtech players due to its business-friendly regulations.

Companies want to seize APAC’s potential for rapid development of medical devices by investing in the right geography that would support their expansion plans.

The country brags of presence of leading medtech companies such as Medtronic, Baxter International, AB Sciex, Becton Dickinson, Biotronik, Hoya Surgical Optics, and Life Technologies that set up their manufacturing plants and R&D units here due to strong patent laws and easy policies to set up and manage a business. For instance, in 2011, Medtronic, one of the world’s largest medical devices manufacturers, opened its first pacemaker and leads manufacturing facility in Singapore, which was the company’s first Asian site manufacturing cardiac devices. As the number of heart patients in APAC rapidly increases, Singapore is a perfect base to offer modern medical facilities to patients across emerging Asian markets.

The medtech sector in Singapore is growing mainly due to government schemes that focus on investing in the sector. With initiatives such as Sector Specific Accelerator (SSA) Program that identifies and invests in high-potential medical technology start-ups (an amount of US$70 million has been committed for the formation and growth of such businesses) and EDBI, the corporate investment arm of the Singapore Economic Development Board that invests in innovative healthcare IT, services, devices, and therapeutics companies, the Singapore government supports the growth of medtech innovation in the country.

The medtech sector in Singapore is growing mainly due to government schemes that focus on investing in the sector.

Apart from setting up committed bodies, the Singapore government in 2015 announced that it would invest US$4 billion in biomedical sciences research for the period between 2015 and 2020 to strengthen the county’s position as Asia’s innovation center.

While Singapore is a favorable location for medtech manufacturing and R&D, it is still a young market that is witnessing problems similar to the ones seen in other APAC countries. Many countries in the region are also capable of contributing to the technological health innovation but face challenges in broadening their reach and lack assertiveness to develop innovative ways to reach a broader range of patients.

Medical device regulations are the key challenge faced by device manufacturers in the Asian region. Med tech industry is regulated by strict guidelines through each phase of product or service development. In several Asian markets, there are no clear guidelines for device manufacturers that classify medical devices as simple or complex, or even mention how to handle them. Irregularities in clearly laid guidelines for introducing and using such products often create problems for companies to come up with advanced solutions in new geographies of the APAC region. Each country has different regulations for quality control, product registration, and pricing, and these are frequently unclear and inconsistent. This is a considerable concern for medtech players planning to set up a shop in the APAC region.

Medical device regulations are the key challenge faced by device manufacturers in the Asian region.

Another hiccup that the manufacturers face is the lack of definitive reimbursement structure. With new innovations in the healthcare domain, expenditure on medical technology is expected to grow but lack of transparent compensation schemes is a major hindrance. Medical device firms, across APAC region, face the challenge of limited clarity on payment structure of technological products and services. For instance, for medical products such as pacemakers and heart valves that are readily available, the reimbursement cost is generally available, but for progressing techniques or products like LVAD (left ventricular assist device), no coverage guidelines have been established. With this lack of clarity on the structure and level of reimbursement on such advanced products, medtech companies find it difficult to place their products in the market at a competitive price.

With unclear regulations and reimbursement policy structure, the medtech companies face a hard time in the APAC region. Competition from local players also add concerns for these players to survive in these markets. Partnerships of local medtech companies with funding firms and other players are on the rise. Domestic companies often partner with private equity firms that invest in and support the local players to innovate and expand. For instance, Huami Corporation, a manufacturer of wearable fitness monitoring devices, attracted investment from American venture capital firm Sequoia Capital and Xiaomi, a Chinese smartphone player, to develop a device that monitors health (tracking the number of steps walked, number of sleep hours, calories consumed, etc.) selling at a sober price of US$15 as compared to the average price of more than US$150 of its competitive brands including Apple and Samsung.

With unclear regulations and reimbursement policy structure, the medtech companies face a hard time in the APAC region. Competition from local players also add concerns for these players to survive in these markets.

Challenges for entering such a diverse market will take time to overcome, but companies are on the lookout for growth platforms and seem to be willing to leave no stone unturned to capture new opportunities. One such opportunity that multinationals can use to their advantage is partnering with regional stakeholders to access the APAC market. These collaborations are not limited to medtech companies or players in the healthcare domain, but are extended to a broader range of players including regional governments, regulatory bodies, educational institutions, insurance companies, and other technology companies.

Med tech companies are partnering with pharmaceutical players to access local market and widen their network. For instance, in India, Roche, a Swiss healthcare company dealing with diagnostic devices, got into a marketing partnership with Indian drug manufacturer Mankind Pharma, to extend the availability and market penetration of its blood glucose monitors, Accu-Check Go, in tier 2 and tier 3 towns making use of Mankind’s extensive local distribution network. Partnerships are critical for multinational players to rapidly and efficiently increase their geographic presence in the APAC region.

Another opportunity that medtech companies can seize to grow is the appointment of local staff in the regional management. Local people have a better market understanding and know how the system works. The decision making capabilities, if lie in the hand of local leaders, can work in favor of the companies as these leaders better understand the way the market functions. Balancing the availability of local talent and brand’s global assets, medtech players can be successful in developing products as per market needs. A mix of local resources and international talent in crucial to oversee operations in unstructured and fragmented markets such as APAC.

EOS Perspective

Correct assessment of the market needs is critical for any business to be successful. For medtech companies, APAC has been a challenging landscape due to fragmented market, as well as unstructured and complex regulatory environments. But with the focus being shifted to the dynamic and fast growing economies of APAC, the medtech market is positive to grow as the region offers scope of development and growth mainly due to aging population and growing income of middle class.

With challenges unique to each geography in APAC, medtech companies are focusing on partnering and collaborating with local medtech players and other stakeholders in the region. With strategic partnerships, global medtech players can reduce the intensity of competition faced from local companies. Collaborating with the right partner in different aspects of product development ensures growth, right product placement, and speedy market expansion. Association with regional entities are expected to increase, witnessing strong growth of the players in the medtech space.

The regulatory landscape in the region is highly fragmented and needs restructuring. Independent organization such as Asia Pacific Medical Technology Association (APACMed), formed in 2014, assigns itself to strike a balance between medtech companies wishing to enter the APAC market and other regional agencies aiming to improve the standard of healthcare offered to patients. Efforts such as these may bring coordination in the regulatory landscape, but it will take long to come to general consensus on similar laws of conducting business in this field.

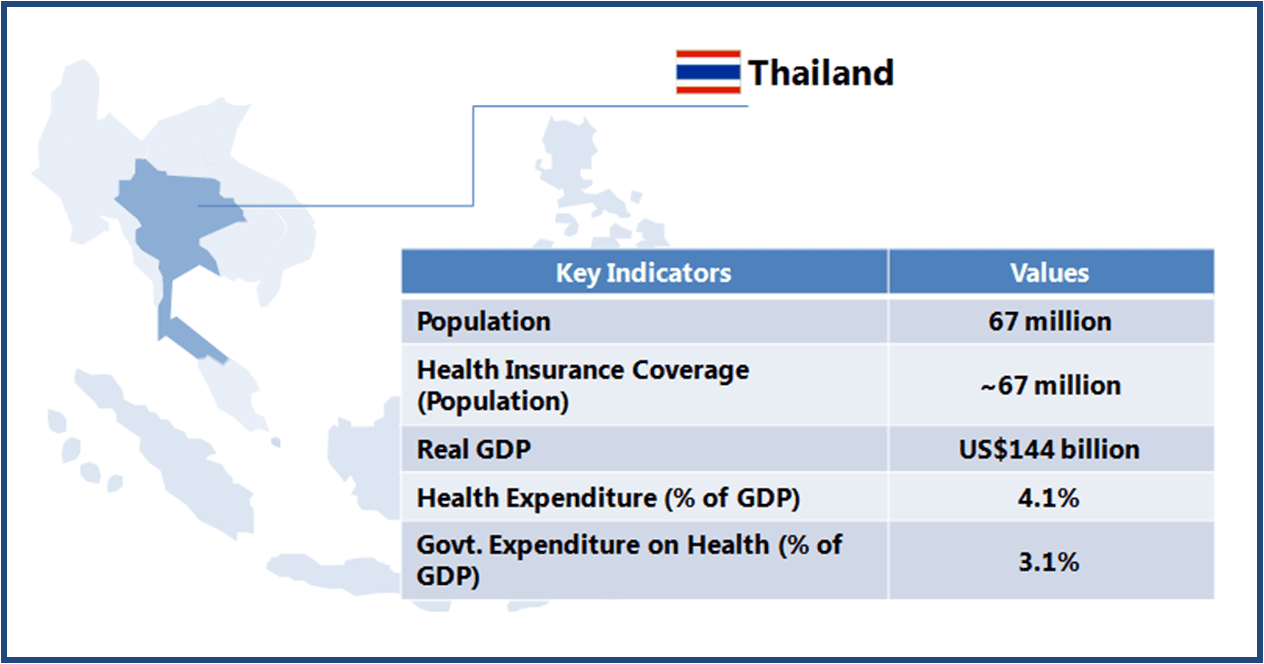

Thailand boasts of world class medical facilities (especially in the private healthcare sector), and is among the world’s largest medical tourism markets. The government is looking to further develop Thailand into an “International Health Center for Excellence” under its second strategic five-year plan (2012-2016).

Thailand boasts of world class medical facilities (especially in the private healthcare sector), and is among the world’s largest medical tourism markets. The government is looking to further develop Thailand into an “International Health Center for Excellence” under its second strategic five-year plan (2012-2016).